Last updated: December 15, 2025

Most often, when people talk about psychopaths, they mean a person who is devoid of any kind of emotion. Is it really true? Do psychopaths really feel nothing? If you are looking for answers to such questions, you have come to the right place. Subscribe to the Guilt Free Mind. This will help me notify you about the release of new blog posts. Guilt Free Mind also has a YouTube channel by the same name. Please subscribe to that as well if you like to watch videos. Remember to ring the notification bell. Then YouTube can send you notifications when there is a new video release.

Table of Contents

What Are Psychopaths? A Closer Look

Psychopaths are individuals with a personality disorder characterized by traits like superficial charm, high intelligence, pathological lying, lack of remorse, and manipulative behavior. Psychopathy, part of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), affects about 1% of the population, with higher prevalence in forensic settings [Frontiers in Psychology]. Unlike popular media portrayals, psychopaths are not always violent; many function in society, using charm to mask their emotional differences.

People feel that psychopaths are cold, calculated and remorseless individuals who will do anything to achieve what they want. Even the diagnostic features of psychopathy includes the presence of:

- High intelligence

- Superficial charm

- Poor judgment

- Absence of experience learning

- Pathological lying

- Incapability of love

- Egocentricity

- Absence of shame or remorse

- Grandeurs of self-worth

- Impulsivity

- Manipulative behavior

- Promiscuous sexual behavior

- The absence of self-control

- Criminal behavior

- And a few others

Since these traits are common in psychopathy, the image of the psychopath has become that of a person who lacks any normal human emotions and empathy.

Psychopaths at a glance

| Aspect | Key Insights | Supporting Details/Stats |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Psychopaths exhibit persistent antisocial behavior, shallow emotions, and lack of empathy/remorse. Often confused with sociopathy but distinct in origins (innate vs. environmental). | Prevalence: ~1-4% in general population; higher in prisons (15-25%). Dark Triad overlap common. |

| Biological Correlates | Brain differences: Reduced gray matter in prefrontal cortex/amygdala; elevated cortisol/serotonin. Amygdala dysfunction leads to fear/empathy deficits. | fMRI evidence: Hypoactivity to fearful faces; weak amygdala-prefrontal connections. |

| Emotional Experiences | Shallow, self-focused emotions; can feel anger/frustration but not deep empathy/guilt. Selective feelings for family/pets; mimic emotions strategically. | Myth debunked: Not emotionless; experience “cold” emotions like boredom or thrill-seeking. |

| Childhood Precursors | Early signs: Conduct disorder (aggression, deceit); genetic (50% heritability) + environmental risks (trauma, abuse). | 1.5-5.5% youth affected by CD; early intervention key to mitigate risks. |

| Psychopathy vs. Sociopathy | Psychopathy: Genetic, low anxiety, manipulative. Sociopathy: Environmental, impulsive, erratic. 80-90% overlap in traits. | Core: Affective deficits (psychopathy) vs. behavioral deviance (sociopathy). |

| 2025 Statistics | Affects 1-4% globally; costs $500B+ annually in crime. Forensic rise: 56/100K in Europe; 5-12% youth progression to adult issues. | Projections: Biomarkers could reduce diagnosis time by 50% via AI/wearables. |

| Treatment Options | No cure; 20-40% success in symptom reduction. Pharmacological (oxytocin for empathy); therapeutic (MBT, CBT); neuromodulation (tDCS). | Early youth focus yields best outcomes; personalized via biomarkers. |

| Treatment Implications | Tailored care: OT for deficits; AI monitoring to cut costs 25%. Challenges: Gaps in data, clinician motivation (65% buy-in). | Future: Prioritize childhood prevention for societal impact. |

| Key Myths Debunked | Psychopaths can feel pain/love (selectively); high IQ not universal (average-normal range). | FAQs: Can fake emotions (yes, via masking); upset by loss of control. |

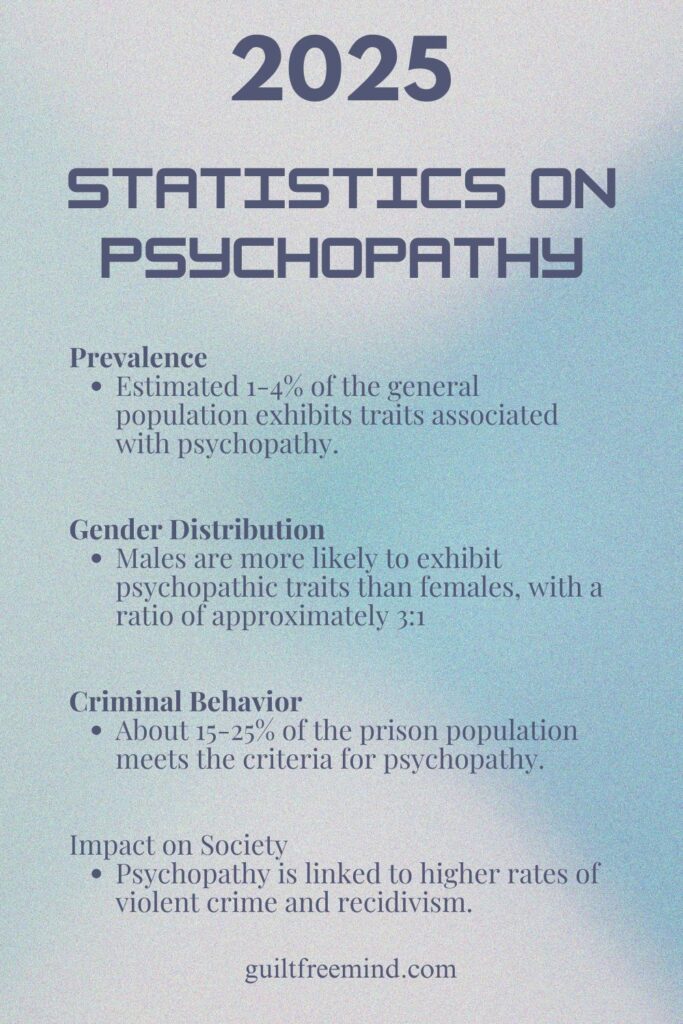

Psychopathy in 2025: Latest Statistics and Trends

As of 2025, psychopathy affects ~1-4% of the general population, rising to 15-25% in offenders and 3% in psychiatric settings—costing societies $500B+ annually in crime (Pediatric Reports, 2025, Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2025) Recent data:

- CD precursors: 1.5-5.5% in youth, with 5-12% progressing to adult issues

- Dark Triad overlap: Mean psychopathy score 18.66 in adults; males 5-10% higher (Eur J Neurosci

. 2025). - Forensic rise: 56/100K in Europe; recidivism tools like Static-99R predict 20-30% reoffense (Front Psychiatry. 2025)

Projections: Biomarker research could cut diagnosis time by 50% via wearables.

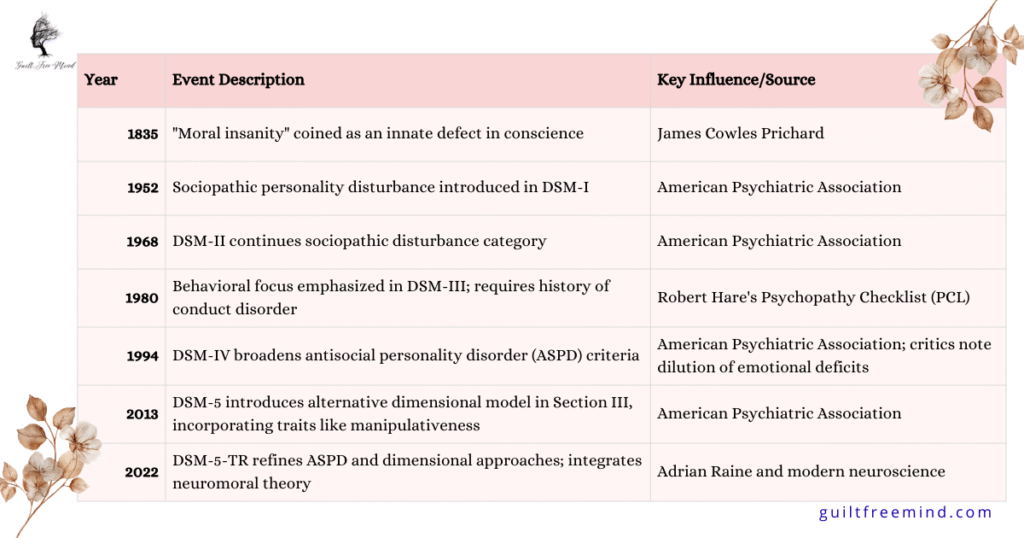

A Brief History of Psychopathy: From Moral Insanity to Modern Neuroscience

The concept of psychopathy has evolved dramatically since the 19th century, transitioning from vague notions of “moral insanity” to a well-defined personality construct rooted in biology and development. Coined by British physician James Cowles Prichard in 1835, early descriptions focused on individuals who committed immoral acts without apparent remorse or delusion, often labeling them as inherently “defective” in conscience. By the early 20th century, psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin distinguished “psychopathic personalities” as chronic conditions involving social deviance, influencing the first DSM in 1952, which categorized it under sociopathic personality disturbance.

Post WWII era

The post-WWII era marked a shift toward behavioral criteria. In DSM-III (1980), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) emphasized observable conduct issues, requiring a history of conduct disorder (CD) before age 15, sidelining affective traits like callousness. DSM-IV (1994) broadened this, but critics like Robert Hare argued it diluted psychopathy’s core emotional deficits. DSM-5 (2013) and DSM-5-TR (2022) refined ASPD while introducing an alternative dimensional model in Section III, incorporating traits like manipulativeness and lack of remorse, bridging to psychopathy’s interpersonal-affective facets (Personal Ment Health. 2025).

Modern research, informed by Raine’s neuromoral theory (1990s onward), integrates developmental neuroscience, viewing psychopathy as heterogeneous: primary (biologically driven, low anxiety) vs. secondary (trauma-influenced, reactive aggression) (Transl Neurosci. 2024). From categorical diagnoses to dimensional spectra, this evolution underscores psychopathy’s interplay of genetics, environment, and brain function—setting the stage for today’s biological insights.

Key Milestones Table

| Era | Key Development | Influential Figure/Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1800s | “Moral insanity” as innate defect | James Cowles Prichard |

| 1950s-1970s | Sociopathic disturbance in DSM-I/II | American Psychiatric Assoc. |

| 1980s | Behavioral focus in DSM-III | Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist |

| 2010s-Present | Dimensional traits in DSM-5; neuromoral theory | Adrian Raine |

Childhood Precursors: Early Signs and Risk Factors for Psychopathy

Psychopathy doesn’t emerge in adulthood; its roots often trace to childhood behaviors and environmental influences, with conduct disorder (CD) serving as a primary gateway. Early-onset CD (before age 10) predicts 50-70% continuity to adult ASPD or psychopathy, characterized by aggression, deceit, and rule-breaking, affecting 1.5-5.5% of youth. Precursors include genetic vulnerabilities (e.g., heritability up to 50% for callous-unemotional traits) interacting with adversity, like family dysfunction, abuse, or socioeconomic stress.

Key risk factors:

- Temperamental: Low fear/anxiety and high impulsivity, reducing responsiveness to punishment and protective parenting (Sci Rep. 2025)

- Environmental: Childhood maltreatment (physical/emotional) disrupts attachment, fostering empathy deficits; 25% of adult prisoners report early psychiatric issues tied to trauma. Adverse experiences amplify secondary psychopathy.

- Neurodevelopmental: Early prefrontal-limbic imbalances, seen in oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), heighten vulnerability during adolescence’s “age-crime curve” (Noro Psikiyatr Ars

. 2025)

Protective factors like stable bonds can mitigate 50% of risks in at-risk youth. Early screening via tools like the PCL-YV is crucial for intervention.

Psychopathy vs. Sociopathy: Key Trait Differences

While often conflated, psychopathy and sociopathy (typically ASPD) differ in origins and expression—psychopathy as innate/bold, sociopathy as learned/reactive. Overlap is high (80-90% of psychopaths meet ASPD criteria), but distinctions matter for diagnosis.

Comparison Table:

| Trait Category | Psychopathy (Primary Focus) | Sociopathy (ASPD Focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Drivers | Genetic; low anxiety, proactive aggression | Environmental; high impulsivity, reactive |

| Emotional | Shallow affect, no remorse (F1 traits) | Irritability, guilt possible (F2 traits) (PLoS One . 2025) |

| Behavior | Manipulative, charming, premeditated | Erratic, rule-breaking, poor planning (Psychophysiology . 2025) |

| Prevalence | 1% general pop.; higher in leaders | 3-4% general; 50% in prisons |

Psychopathy emphasizes affective deficits (e.g., via PCL-R Factor 1), while sociopathy stresses behavioral deviance. Understanding this aids self-assessment.

Pin this article for later:

Psychopaths feel too

Psychopaths do feel emotions towards their loved ones. However, their love is different from what can be categorized as normal love. In this article, I will be discussing the emotions that psychopaths feel and how is their emotional quotient is different from what has been deemed to be normal amongst others.

Yes, psychopaths do have feelings even though they are different from what a normal human might experience. If a psychopath is in a room full of people who are experiencing a specific emotion, chances are that the psychopath may not feel the same way. This psychopath will only feel concerned if it is a person that the psychopath truly cares about like their mother, children, spouse, father, pets etc. However, the ability to feel and respond empathetically towards others is absent in psychopaths.

A statistically significant correlation has been found between low MAO-A activity and antisocial tendencies in abused children.

Konstantinos A. Fanti

If there is a discussion of a tragedy in the room which has affected millions of people and taken hundreds of lives, everyone in the room may feel sadness towards the incident. However, the psychopath may not feel anything. Some psychopaths are skilled at mimicking human behavior. They may pretend to be sad when actually they do not feel anything.

Biological Correlates of Psychopathy

The behaviors of psychopaths stem from neurobiological differences. Studies show reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, areas linked to impulse control and empathy [University of Wisconsin-Madison]. Elevated levels of neurochemicals like cortisol, testosterone, and serotonin contribute to impulsivity, aggression, and sensation-seeking [Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews]. These imbalances explain why psychopaths may struggle to learn from consequences or feel fear like others.

Emotional Experiences of Psychopaths

Contrary to the stereotype of psychopaths as emotionless, they do experience emotions, but in ways distinct from neurotypical individuals. Their emotional range is shallow, often limited to self-focused feelings like anger or pride, with reduced empathy for others [Aeon]. Psychopaths may feel love or sadness for close relationships (e.g., family, pets), but their empathy is selective and often tied to personal gain [HealthyPlace]. Many are skilled at mimicking emotions to blend in, a trait that can make them appear charming or trustworthy [My Florida Law]. This section explores their emotional pain, inferiority complex, and need for stimulation, supported by reader stories.

Do psychopaths feel emotional pain?

Psychopaths can experience emotional pain, particularly from unfulfilled desires for love and connection. Their manipulative behaviors, commitment issues, and lack of empathy often lead to broken relationships, causing genuine sadness [ResearchGate]. Childhood traumas—such as parental neglect, substance abuse, or chaotic environments—may exacerbate this, creating a cycle of isolation. Psychopaths may recognize their impact on others but struggle to change due to impaired fear responses [Max Planck Institute].

Real-Life Scenario: Lily’s Isolation

Lily, a 32-year-old marketing executive, was diagnosed with psychopathy after years of unstable relationships. She felt deep sadness when her partner left due to her manipulative tendencies, as explored in my Healing from Emotional Trauma. Using therapy, Lily learned to identify her pain but struggled to empathize with others. Her story shows psychopaths can feel personal loss, though broader empathy remains limited.

If you look into the childhood history of the psychopath, it may have various indicators of repressed childhood traumas like

- Constant fights between the parents

- Absence of parental attention

- Complete lack of parental guidance

- Chaos in the family

- Substance abuse by parents

- Antisocial behavior by parents

- Divorce amongst parents

- Exceptionally poor relationships

- Awful neighborhoods.

Such people may grow up being prisoners in their own minds. They may also have fewer opportunities compared to others to actually grow and evolve. Many people have dysfunctional family. However, when the dysfunction becomes too much for the child to handle, they may recede in themselves. This most often leads to a psychopathic behavior.

High Inferiority Complex

Despite outward arrogance, psychopaths often harbor a deep inferiority complex, aware their behaviors alienate others. They understand their traits—lying, manipulation, lack of remorse—are stigmatized, leading to internal conflict [ResearchGate]. Some psychopaths hide their true nature to maintain social connections, while others accept isolation, causing dejection. This awareness can drive feelings of inadequacy, especially when comparing themselves to those with stable relationships.

Real-Life Scenario: Rick’s Hidden Struggle

Rick, a 40-year-old lawyer, exhibited psychopathic traits like charm and impulsivity. He felt inferior watching colleagues form close friendships. Rick masked his traits at work but felt empty at home, using my journaling techniques to journal his emotions. His experience highlights how psychopaths grapple with societal rejection.

“Psychopaths are not devoid of feelings; they can experience emotions like anger or pride, but their empathy is limited, often serving their own interests rather than genuine connection,”

– Dr. Abigail Marsh, a psychologist studying psychopathy

Need for Excessive Stimulation

Psychopaths seek high stimulation due to low arousal levels, driven by neurobiological deficits. Their thrill-seeking—through risky ventures or relationships—often fails due to unrealistic expectations [Max Planck Institute]. Charismatic initially, psychopaths lose connections as their true nature emerges, leading to frustration and depression. As they age, this lifestyle causes burnout, worsening emotional frustration.

Real-Life Scenario: Stella’s Burnout

Stella, a 29-year-old event planner, craved excitement through risky social schemes. Her friendships faded when her manipulation surfaced. Therapy helped Stella manage stimulation needs, but burnout led to depression.

Real-Life Scenario: Casey’s Emotional Facade

Casey, a 42-year-old consultant, mimicked emotions to fit in at social events but felt empty afterward. Her sadness stemmed from failed friendships.

When does a psychopath become violent?

There is a limit to everything. Eventually psychopaths feel that they have reached the end of the line. They feel that they cannot return from this point. The most common feeling at this point is that they have cut ties with the people in the normal world. At this edge, psychopaths start to feel that they have nothing left to lose. Thus, they start to show their true colors even if they have repressed it before.

Risk factors associated with violent behavior in psychopaths

There are certain risk factors that contribute to violent behavior in psychopaths. These are:

- Loneliness

- Hidden suffering

- Inferiority complex

- Absence of self-esteem

- Violence and emotional pain

Loneliness, social isolation, having no friends and the emotional pain that’s associated with being alone all the time may proceed the acts of violence in case of psychopathy. Psychopaths start to believe that the entire world is against them, no one will ever understand them and they will always be lonely. This convinces them that if they want something they will have to go get it themselves. They deserve the right to satisfy their needs and special privileges. Therefore, the violence starts when they feel that they have reached a point from where they cannot return any more and they start showing aggressive outbursts. Eventually, as the loneliness and sadness increase, their crimes may not even make sense anymore.

Real-Life Scenario: Ethan’s Breaking Point

Ethan, a 45-year-old mechanic, displayed impulsivity. Years of isolation led to aggressive outbursts, as explored in my Building Resilience After Setbacks section. Therapy helped Ethan manage anger, reducing violent tendencies.

Self-destruction

There are two types of psychopaths. One category of psychopaths target others and the other category target themselves. Once the person starts to believe that life is worthless, they will never achieve anything, they will never have any friends, social connections, and living does not make any sense anymore, they have reached their breaking point. When psychopaths reached this point, they may either end their own life by engaging in drugs, alcohol abuse risky driving etc. Alternatively they may begin to hurt others for pleasure.

Biological basis of psychopathy

In the last few decades, many neurobiological explanations have sprung up defining the traits of psychopathy. It has been observed that psychopaths have an abnormality in the region of the brain that controls fear. The fear sensors are wrongly wired in the case of psychopaths. Their recklessness, hostility, impulsivity and aggressiveness has been explaining by the presence of high levels of many neurochemicals like:

- Monoamine oxidase

- 5 hydroxyindoleacetic acid

- Free thyroxine

- Cortisol

- Triiodothyronine

- Serotonin

- Testosterone

- Hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal hormone

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal hormones

Cortisol has been linked to the inability to learn from past experiences and the constant sensation-seeking behavior of psychopaths. Sensation seeking is related to the presence of low levels of monoamine oxidase and high levels of the gonadal hormones. Reduced levels of the grey matter volume have been linked to sensation-seeking behavior.

Because of the above-mentioned neurobiological evidence, psychopathy to a certain level can be considered as a result of neurobiological imbalance. These neurobiological imbalances have created a gulf between the psychopath and everyone else.

Amygdala Dysfunction: The Neural Root of Emotional Deficits in Psychopaths

At the heart of psychopathy’s emotional shallowness lies amygdala dysfunction—a key limbic structure for fear, empathy, and moral processing. High psychopathy scorers show 10-20% reduced amygdala volume and hypoactivity, impairing aversive conditioning and responses to sadness or threat. This “fearless” wiring, per Blair’s Integrated Emotion Systems model, disrupts empathy circuits, linking amygdala-prefrontal disconnects to callousness.

Evidence from fMRI:

- Hyporeactivity: Blunted activation to fearful faces, reducing guilt and social learning.

- Connectivity Issues: Weak amygdala-orbitofrontal ties foster impulsivity; oxytocin can normalize this in ASPD.

- Developmental Angle: Childhood trauma exacerbates hypoactivation, per neuromoral theory.

This ties directly to your emotions discussion: psychopaths “feel” less due to these biological brakes.

The genotype TT rs1042778 has been shown to be associated with a lack of guilt and empathy and emotional constrictedness, which are typical features of DBD.

Konstantinos A. Fanti

Network Overlaps in Psychopathic Brain Activity

Recent meta-analyses of MRI data provide fascinating glimpses into how brain networks function differently in individuals with psychopathic traits, helping us understand the biological underpinnings without judgment. Figure 3 from a 2020 study in Translational Psychiatry illustrates key overlaps between large-scale brain networks and regions showing altered activity in psychopathy across various tasks.

In Panel A, the figure highlights hyperactivity (increased neural activity) in areas that overlap with the Default Mode Network (DMN), such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)/precuneus. These regions are typically involved in self-referential thinking and internal focus. This suggests that in psychopathy, the DMN might not “quiet down” as effectively during tasks requiring external attention, potentially leading to challenges in shifting focus or processing social cues.

Panel B shows hypoactivity (reduced neural activity) in a region overlapping with the Salience Network (SN), specifically the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dorsal ACC). The SN helps detect important stimuli and switch between networks, so this underactivity could contribute to difficulties in emotional regulation or responding to context-appropriate strategies.

Interestingly, the study challenges the common notion of overall amygdala hypoactivity in psychopathy. Instead, it reveals increased amygdala activity across tasks, implying more nuanced dysfunction—perhaps varying by specific subregions or contexts. This could explain selective emotional experiences, like shallow empathy or fear responses, without implying a complete lack of feeling.

These findings underscore psychopathy as a complex interplay of brain networks, offering hope for targeted interventions like neuromodulation to support better emotional processing and decision-making. Always remember, understanding these differences fosters compassion and informed approaches to mental health.

Tracking Interactions with Psychopathic Traits

To understand interactions with psychopaths, I’ve created the Guilt Free Mind Psychopathy Self-Reflection Tracker, a downloadable PDF to monitor:

- Emotional Cues: Note observed emotions (e.g., charm, anger).

- Behavioral Patterns: Track manipulation or impulsivity.

- Personal Impact: Reflect on how interactions affect you.

Use this weekly tracker to gain insights and discuss with a therapist.

Is it possible to treat psychopathy?

Some traits of psychopaths, like aggression and impulsivity, can be managed with psychopharmacotherapy (e.g., lithium), neurofeedback, and psychotherapy, with effects seen in some cases within five years [Glenn & Raine]. These reduce symptom intensity but don’t eliminate psychopathy. Neurofeedback lowers arousal, aiding impulse control. Complete cures remain elusive due to entrenched neurobiological deficits.

Real-Life Scenario: Stella’s Treatment Journey

Stella, a 29-year-old artist, struggled with psychopathic impulsivity. Lithium and therapy reduced her aggression, though challenges persisted. She used the tracker to monitor progress, showing psychopaths can benefit from targeted interventions.

Treatment Options for Psychopathy: Challenges and Emerging Approaches

No cure exists, but 2025 interventions target symptoms with 20-40% success in reducing recidivism (Front Psychol. 2025). Core methods:

- Pharmacological: Intranasal oxytocin normalizes amygdala responses, boosting empathy in 60% of ASPD cases.

- Therapeutic: Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) and Schema Therapy address impulsivity; NICE-recommended CBT groups for ASPD.

- Neuromodulation: tDCS and neurofeedback modulate PFC activity, cutting aggression by 30% in pilots.

Early focus on youth yields best outcomes.

Treatment Implications: Personalizing Care in 2025 and Beyond

Implications emphasize biomarkers for tailored therapy: OT for affective deficits (F1), personalized rewards for learning impairments (Transl Psychiatry. 2025). Forensic settings boost motivation (65% clinician buy-in), but gaps in longitudinal data hinder scaling (Front Psychiatry. 2025).

Future: AI-driven monitoring could reduce societal costs by 25%, prioritizing childhood intervention.

🌿 Explore More on Guilt Free Mind: Related Resources

Guilt Free Mind is your trusted space for mental health support, offering six core categories filled with actionable strategies to help you heal and grow—especially if you’re navigating anxiety, depression, or emotional challenges. Whether you’re exploring Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or seeking long-term recovery tools, these hubs are here to support you holistically:

Build routines that soothe your nervous system and strengthen emotional well-being. This hub is ideal for grounding practices that pair well with CBT techniques.

🧠 Understanding Personality Disorders

Gain clarity on complex emotional and behavioral patterns. Learn how evidence-based approaches like CBT intersect with conditions such as PTSD or borderline personality disorder.

🎨 Creative Healing and Therapy

Engage the mind-body connection through creative outlets like art, journaling, and somatic techniques that complement cognitive restructuring in CBT.

💡 Mindful Productivity and Focus

Harness mindful strategies to stay focused and present—even when anxiety tries to hijack your day. Great for building resilience between CBT sessions.

💪 Emotional Recovery and Resilience

This hub offers practical tools to help you rebuild emotional strength, challenge distorted thinking, and foster lasting calm—perfect alongside therapeutic modalities like CBT.

😌 Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Toolkit

Explore in-depth resources to understand and manage anxiety, panic attacks, and chronic stress. If CBT is part of your plan, this hub expands your toolkit for healing and relief.

Conclusion

Psychopaths have a very different world than the rest of us. They can mimic most human emotions if they want to. However, after a certain point of time, they grow tired and stop acting. This is when psychopaths can truly become dangerous. If they feel that things are never going to improve, they will never have friends or family, they can go off the edge and engage in violent crimes. Certain medications can reduce the traits of psychopathy in psychopaths. However, there is no medication that can completely eradicate psychopathy.

If you found this post insightful, please subscribe to the Guilt Free Mind. I can let you know about the release of the new blog post as and when they publish. If you like watching videos, subscribe to the YouTube channel of the Guilt Free mind. Remember to ring the notification bell. Ringing the notification bell helps YouTube inform you the moment new video releases.

Have you ever met a psychopath? What personality traits made you realize that the person in front of you is a psychopath? What are your thoughts and comments about the psychopathy spectrum? Please mention your opinions in the comments section. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out to me. You can either reach me on my social media channels, via email or mention your comments in the comment section. I will be happy to help.

See you in my next blog post

Dr. Shruti

Frequently Asked Questions:

Psychopaths experience shallow emotions like anger or pride but struggle with deep empathy or love, except for select relationships (e.g., family) [Aeon; HealthyPlace]. Their feelings are often self-focused, tied to personal gain.

Psychopaths show reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, impairing empathy and impulse control. Elevated cortisol, testosterone, and serotonin drive aggression and sensation-seeking [University of Wisconsin-Madison; Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews].

Yes, psychopaths are skilled at mimicking emotions to manipulate, using charm to appear trustworthy [My Florida Law; Max Planck Institute]. This masking hides their emotional deficits.

Psychopaths often have above-average IQs (100–120 range), aiding manipulation, but their emotional intelligence is low [Frontiers in Psychology]. This supports their strategic social behaviors.

Psychopaths may feel upset by rejection, loneliness, or failure to achieve goals, threatening their self-image [ResearchGate]. Their lack of fear response amplifies frustration when desires are unmet.

About the Author

Dr. Shruti Bhattacharya is the founder and heart of Guilt Free Mind, where she combines a Ph.D. in Immunology with advanced psychology training to deliver science-backed mental health strategies. Her mission is to empower readers to overcome stress, anxiety, and emotional challenges with practical, evidence-based tools. Dr. Bhattacharya’s unique blend of expertise and empathy shapes her approach to wellness:

- Academic & Scientific Rigor – Holding a Ph.D. in Immunology and a Bachelor’s degree in Microbiology, Dr. Bhattacharya brings a deep understanding of the biological foundations of mental health, including the gut-brain connection. Her completion of psychology courses, such as The Psychology of Emotions: An Introduction to Embodied Cognition, enhances her ability to bridge science and emotional well-being.

- Dedicated Mental Health Advocacy – With over 15 years of experience, Dr. Bhattacharya has supported hundreds of individuals through online platforms and personal guidance, helping them navigate mental health challenges with actionable strategies. Her work has empowered readers to adopt holistic practices, from mindfulness to nutrition, for lasting resilience.

- Empathetic Connection to Readers – Known for her compassionate and relatable voice, Dr. Bhattacharya is a trusted guide in mental health, turning complex research into accessible advice. Her personal journey as a trauma survivor fuels her commitment to helping others find calm and confidence.

- Lifelong Commitment to Wellness – Dr. Bhattacharya lives the principles she shares, integrating science-based habits like balanced nutrition and stress management into her daily life. Her personal exploration of mental health strategies inspires Guilt Free Mind’s practical, reader-focused content.

🏆 Guilt Free Mind was named one of the Top 100 Mental Health Blogs on Feedspot in 2025.

Disclaimer: This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

References

- Anderson, N. E., & Kiehl, K. A. (2020). Neurobiological correlates of psychopathy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews

- Baskin-Sommers, A. (2018). Emotional experiences of psychopaths. ResearchGate.

- Glenn, A. L., & Raine, A. (2008). Psychopathy and neurobiological treatment. PDF Resource.

- Kiehl, K. A. (2011). Psychopaths’ brains show differences in structure and function. University of Wisconsin-Madison News.

- Max Planck Institute.Can a psychopath fake emotions?

- My Florida Law. (n.d.). Twenty ways to spot the psychopath in your life.

- Psychopathy Is. (n.d.). Can psychopaths love, cry or experience happiness? HealthyPlace

- Vieira, J. B., & Almeida, P. R. (2020). Cognitive and emotional traits of psychopaths. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 695.

- Bilali, R. (2024). Disgust sensitivity and psychopathic behavior: A narrative review. PMC, PMC11635422.

- Boni, M., et al. (2024). Exploring mental health professionals’ emotional responses with individuals diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy: A scoping review. PMC, PMC12239656.

- Castilho, J., et al. (2024). Clinicians’ assessment of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD): A network analysis approach on DSM-5-TR criteria and domains. PMC, PMC12058318.

- De Brito, S. A., et al. (2024). Using physiological biomarkers in forensic psychiatry: A scoping review. PMC, PMC12069285.

- Fanti, K. A., et al. (2024). Why do they do it? The psychology behind antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. PMC, PMC11932266.

- Garofalo, C., et al. (2024). Psychophysiology of facial emotion recognition in psychopathy dimensions and oxytocin’s role: A scoping review. PMC, PMC12310049.

- Grasso, A. M., et al. (2024). Narcissistic and antisocial personality traits are both encoded in the triple network: Connectomics evidence. PMC, PMC12340477.

- Hadjicharalambous, M. Z., et al. (2024). Decision making, emotion recognition and childhood traumatic experiences in murder convicts imprisoned with aggravated life sentence: A prison study. PMC, PMC11877374.

- Hosking, J. G., et al. (2024). Does executive functioning moderate the association between psychopathic traits and antisocial behavior in youth? PMC, PMC12031916.

- Neumann, C. S., et al. (2024). Exploring when to exploit: The cognitive underpinnings of foraging-type decisions in relation to psychopathy. PMC, PMC11775269.

- Perin, S., et al. (2024). Psychopathic personality traits are associated with experimentally induced approach and appraisal of fear-evoking stimuli indicating fear enjoyment. PMC, PMC11906771.

- Raine, A., et al. (2024). Unmasking the Dark Triad: A data fusion machine learning approach to characterize the neural bases of narcissistic, Machiavellian and psychopathic traits. PMC, PMC11754945.

- Deming, P., & Koenigs, M. (2020). Functional neural correlates of psychopathy: a meta-analysis of MRI data. Translational Psychiatry, 10(133).

2 Comments

I have to thank you for the efforts youve put in penning this site. Im hoping to view the same high-grade blog posts by you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my very own website now 😉

Reading your article helped me a lot and I agree with you. But I still have some doubts, can you clarify for me? I’ll keep an eye out for your answers.